HKCO

Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra Environmental, Social and Governance Artistic Director and Principal Conductor for Life Orchestra Members Council Advisors & Artistic Advisors Council Members Management Team Vacancy Contact Us (Tel: 3185 1600)

Concerts

Education

The HKCO Orchestral Academy Hong Kong Youth Zheng Ensemble Hong Kong Young Chinese Orchestra Music Courses Chinese Music Conducting 賽馬會中國音樂教育及推廣計劃 Chinese Music Talent Training Scheme HKJC Chinese Music 360 The International Drum Graded Exam

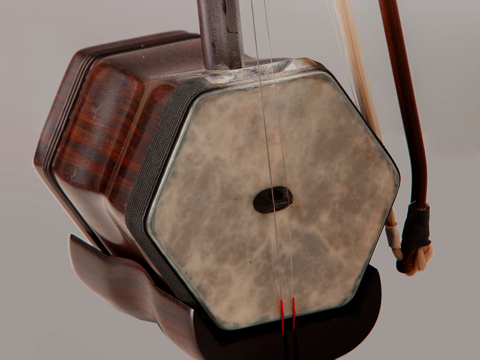

Instrument R&D

Eco-Huqins Chinese Instruments Standard Orchestra Instrument Range Chart and Page Format of the Full Score Configuration of the Orchestra

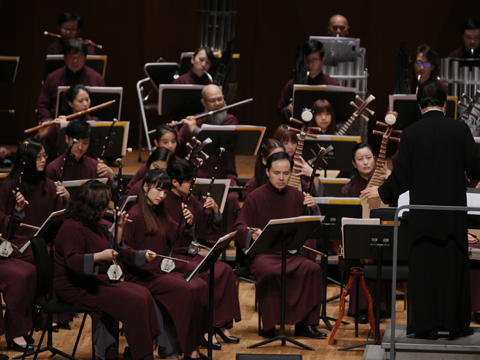

46th Orchestral Season

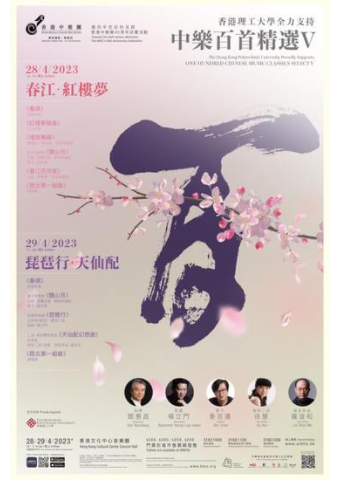

One Hundred Chinese Music Classics Select V

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Proudly Supports

Guan: Qin Jitao

Eco-Erhu: Xu Hui

Eco-Gehu: Lo Chun Wo

The Chorale of Spring Ng King-pan

The Dream of the Red Chamber Suite Wang Liping

1. The Red Chamber Lament

2. The Song of Qingwen

3. The Funeral Procession

4. Grannie Liu

5. The Love between Baoyu and Daiyu

6. The Lantern Festival

7. Dear Ones Parted

8. Burying the Flowers

Dance of the Yao Tribe Liu Tieshan & Mao Yuan Arr. by Peng Xiuwen

Guan and Orchestra The Moon over Guanshan Ancient tune Arr. by Zhang Ying and Yan Huichang

Guan: Qin Jitao

Moonlight on the Spring River Ancient Melody Arr. by Qin Pengzhang and Luo Zhongrong

Northwest Suite Tan Dun

The first section: God in Heaven Grants Us Sweet Rain

The second section: Rousing Games in the Bridal Chamber

The third section: I Miss My Dear Love

The fourth section: Stone-slab Waist Drums

The concert runs approximately 75 minutes without intermission.

The Chorale of Spring Ng King-pan

Guan and Orchestra The Moon over Guanshan Ancient tune Arr. by Zhang Ying and Yan Huichang

Guan: Qin Jitao

Double Concerto for Erhu and Gehu

The Seventh Fairy Maiden Fantasia Wu Hua

1. Descending to the Mortal World: andante espressivo and allegro con allegrezza

2. Returning Home: allegretto scherzando

3. A Tearful Farewell: sorrowful yaoban and presto

Eco-Erhu: Xu Hui

Eco-Gehu: Lo Chun Wo

Music and Recitation

The Story of the Pipa Gu Guanren Poem by Bai Juyi (Tang Dynasty)

Recitation: Raymond Young Lap-moon

Northwest Suite Tan Dun

The first section: God in Heaven Grants Us Sweet Rain

The second section: Rousing Games in the Bridal Chamber

The third section: I Miss My Dear Love

The fourth section: Stone-slab Waist Drums

The concert runs approximately 75 minutes with 15-minute intermission.

tap it out." (Fuller, 2018: 51-52)

To the ancients, poetry, song and dance were all used to express one’s inner feelings. They may have been different in their forms of expression, but they often complemented each other and could be blended seamlessly. Chinese poetry has always placed emphasis on rhythm and rhyme since ancient times, from The Book of Songs to the poems of the Tang Dynasty. The yuefu of the Han dynasty and the ci of the Song dynasty were also poems that could be set to music to be sung. This is evidenced by the captions of the yuefu poems and set pieces in the ci poems.

The programme of this concert by the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra includes exemplary pieces of how poetry and music can complement each other. The Moon over Guanshan, a yuefu music piece dating back to the Han Dynasty is one brilliant narrative. It tells of the sadness of a soldier on the battlefield at the frontier who is doomed never to return. Li Bai (701 - 762) was inspired by it to write a poem, The Moon over Guanshan, in the format of five-character verses that echo ancient poetry. The poem is as follows:

(Chinese only)

The poem translates the emotions in the tune into words, allowing the tragic sentiments to strike at the listener’s inmost heart.

Another ancient tune, Moonlight on the Spring River, has been attributed to the yuefu music of the early 3rd century CE to the late 6th century CE. The poet Zhang Ruoxu of the Tang Dynasty did not adopt the original tune, but the motif inspired him to compose a long seven-word poem, using the river as the scene and the moon as the main subject to depict a beautiful, tranquil, expansive and slightly mysterious moonlit night on the spring river. It expresses the feelings of the wanderer who misses his home as well as his ruminations on life:

(Chinese only)

春江潮水連海平,

海上明月共潮生。

灩灩隨波千萬里,

何處春江無月明?

江流宛轉遶芳甸,

月照花林皆似霰。

空裏流霜不覺飛,

春江潮水連海平,

海上明月共潮生。

灩灩隨波千萬里,

何處春江無月明?

江流宛轉遶芳甸,

月照花林皆似霰。

空裏流霜不覺飛,

汀上白沙看不見。

江天一色無纖塵,

皎皎空中孤月輪。

江畔何人初見月,

江月何年初照人?

人生代代無窮已,

江月年年祇相似。

不知江月待何人?

但見長江送流水。

白雲一片去悠悠,

青楓浦上不勝愁。

誰家今夜扁舟子,

何處相思明月樓?

可憐樓上月徘徊,

應照離人妝鏡臺。

玉戶簾中卷不去,

擣衣砧上拂還來。

此時相望不相聞,

願逐月華流照君。

鴻雁長飛光不度,

魚龍潛躍水成文。

昨夜閒潭夢落花,

可憐春半不還家。

江水流春去欲盡,

江潭落月復西斜。

斜月沉沉藏海霧,

碣石瀟湘無限路。

不知乘月幾人歸,

落月搖情滿江樹。

A programme highlight of this concert is an excerpt from The Dream of the Red Chamber Suite. The Dream of the Red Chamber is one of the four great classical novels of China, and has a monumental influence in the history of Chinese literature. It was made into a television drama series by CCTV in 1987, and it has preserved, to a large extent, the essence of the original novel. The series has been described as a "masterpiece in the history of Chinese television" and an "unparalleled classic". The soundtrack music was composed by renowned lyricist-composer, Wang Liping. It took him four years to complete and is equally regarded as an unparalleled opus in his repertoire. The song Burying the Flowers alone took Mr Wang a year and nine months to write, and is, in his own words, the most emotionally invested piece. It is also one of the most celebrated poems in the novel itself. It traces the intricate emotional shifts of Lin Daiyu, from first seeing the fallen flowers on the ground and lamenting the sight, to feeling sorry for her life. The flowers are used as an analogy for a living person – in this case, herself. The verses incorporate Daiyu’s personal experiences, her fate and her feelings into the scene, expressing her lament for love, life and death. This poem can be considered as the gist of everything about the fictional character of Lin Daiyu; it offers important clues to the author as maker and the reader as perceiver in understanding the character in the round, as well as hints at the character's eventual end. As we listen to the musical interpretation by the orchestra while reading the lyrics here, we may gain much more insight into the protagonist’s tormented heart:

(Chinese only)

紅消香斷有誰憐?

遊絲軟系飄春榭,

落絮輕沾撲繡簾。

閨中女兒惜春暮,

愁緒滿懷無釋處。

手把花鋤出繡簾,

忍踏落花來複去。

柳絲榆莢自芳菲,

憐春忽至惱忽去,

至又無言去未聞。

Your Support

Friends of HKCO

Copyright © 2026 HKCO